When winter arrives, heating costs often become the largest single expense in venue operations. For many investors and operators, one question is becoming increasingly important:

Is there a venue solution that keeps users comfortably warm in winter and genuinely saves energy?

Air domes are emerging as a compelling answer.

Using Broadwell air domes as an example, this article explains—through heating solutions, energy-use comparison, and key energy‑saving technologies—why air domes have clear winter heating advantages over traditional buildings.

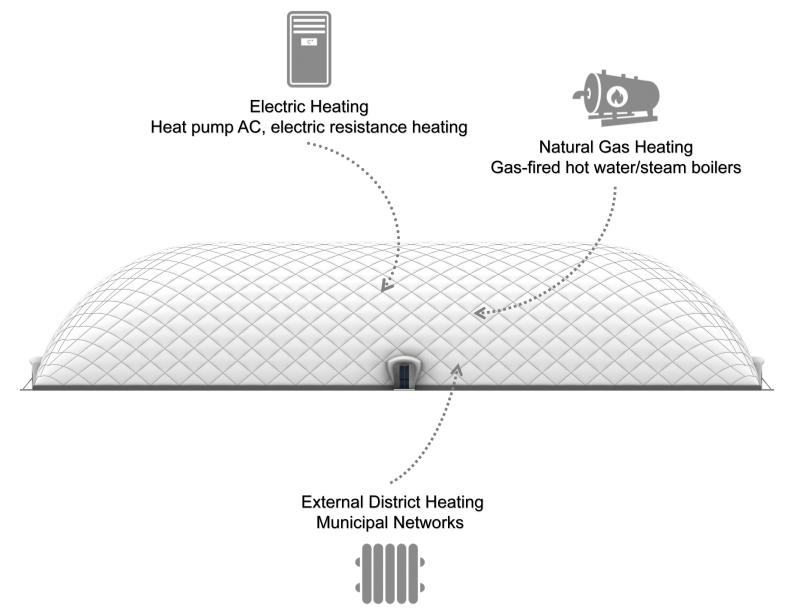

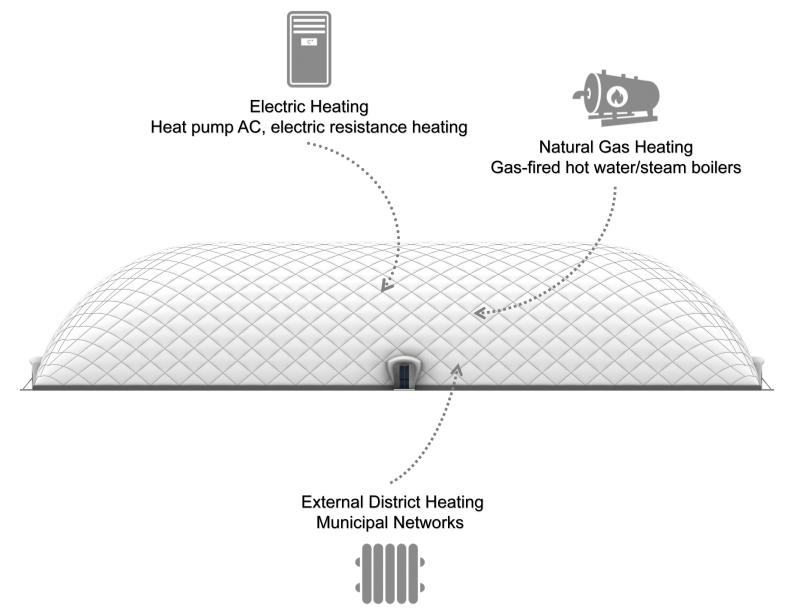

What Heating Options Do Air Domes Have?

Heating systems for air domes are generally categorized by heat source: electricity, natural gas, and external district heating.

1. Electric Heating

Typical forms:

a. Heat pump air conditioning (warm air heating, hot water heating)

b. Electric resistance heating (electric boilers, electric heating coils)

Advantages:

a. Precise temperature control and flexible start/stop.

b. No on‑site combustion, safer and more environmentally friendly

c. Ideal for areas without natural gas or with strict environmental requirements.

d. Heat pumps offer lower energy use, with a COP (i.e., coefficient of performance) of about 1.50–3.00, significantly better than electric resistance heating (COP ≈ 0.95).

Considerations:

a. Electric resistance heating uses a lot of energy. And it is restricted by energy‑efficiency policies in many countries (including China), except in specific scenarios.

b. Requires additional investment in electrical capacity and related equipment.

2. Natural Gas Heating (Primarily Hot‑Water Systems)

Typical forms:

a. Gas‑fired hot water or steam boilers, used with:

i. Underfloor heating coils

ii. Radiators

iii. Fan‑coil units

iv. Air‑handling units

b. Air‑to‑air direct‑combustion heaters

Advantages:

a. High energy content: about 1 m³ of natural gas ≈ 10 kW·h of heat output.

b. High‑efficiency combustion equipment with fast response and quick start/stop.

c. In regions where gas is cheap and electricity is expensive, the cost per unit of heat is lower than with electric heating.

Considerations:

a. Gas connection and safety systems must be designed and installed to meet regulations.

b. Boiler systems require regular inspection and maintenance.

3. External District Heating (Municipal Networks)

Typical form:

a. Connecting the air dome to a municipal or industrial‑park district heating network

b. Heat is transferred to the dome via a heat‑exchange station and hot water pipelines

Where such networks are available, this is often the preferred option:

a. Lower initial investment

b. Simple, stable operation

c. Lower and more predictable operating costs

In addition to these mainstream heat sources, special solutions such as solar thermal or propane‑fired systems can be used in particular projects.

In practice, the heating solution for an air dome should be customized based on:

a. Local gas and electricity prices

b. Availability of district heating

c. Operating hours and season length

d. Function and usage requirements of the venue

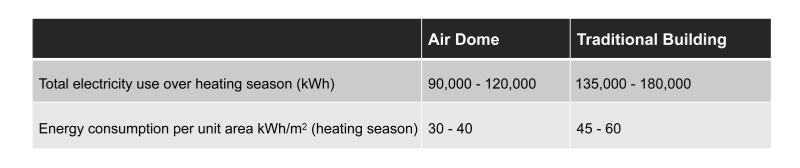

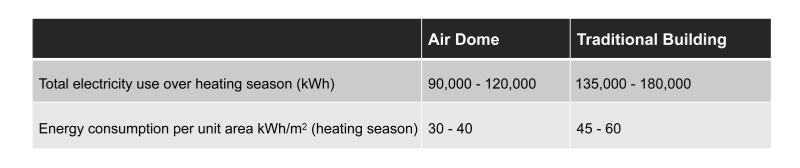

Energy Use: Air Dome vs. Traditional Building

Let us take a 3,000 m² venue as an example.

Assume:

a. Warm‑air air‑conditioning heating

b. Heating season: 120 days (about 4 months)

c. Daily operation: 12 hours

d. Indoor design temperature: 18–20°C

Estimated energy consumption:

Under the same floor area and similar warm‑air AC heating, an air dome typically uses 30%–40% less heating energy per season than a conventional building.

Why Do Air Domes Use Less Energy in Winter?

Traditional reinforced concrete buildings have many beams, columns, and joints. These create numerous thermal bridges and gaps, resulting in heat loss.

Air domes work differently:

a. They use double‑layer or multi‑layer membrane materials.

b. An internal insulation layer forms a continuous building envelope.

c. No beams or columns are penetrating the envelope.

As a result:

a. Thermal bridges are greatly reduced.

b. Air leakage is minimized.

c. Heat loss is significantly lower.

They make air domes inherently more energy efficient. The longer the venue operates each season, the more obvious the energy‑saving advantage becomes.

Broadwell has drawn on extensive real‑world project experience to refine its winter heating solutions continually and has developed a mature suite of energy‑saving technologies, including:

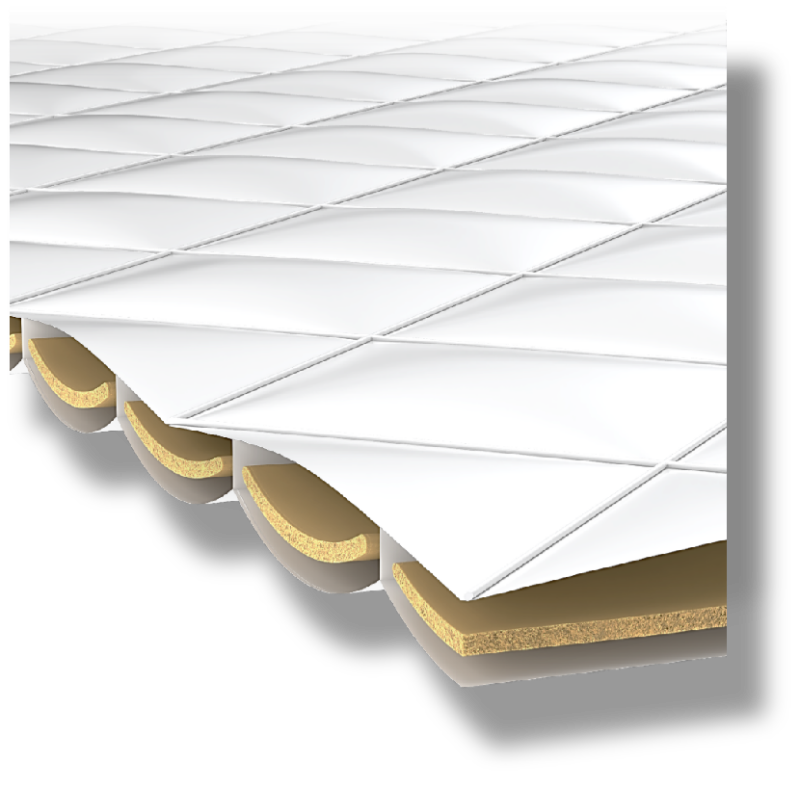

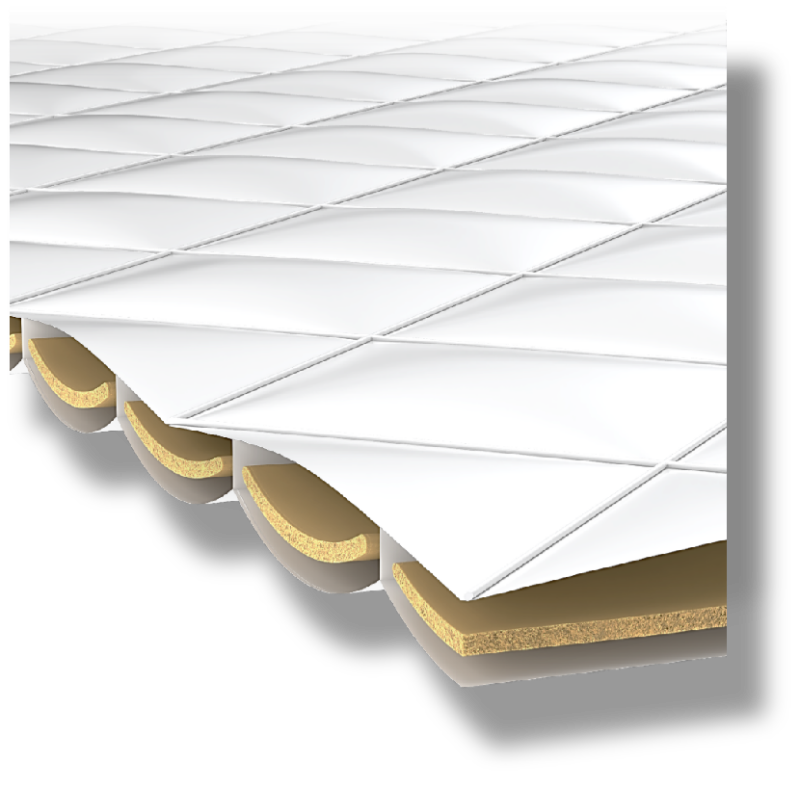

1. R‑Plus Patented Thermal Insulation Technology

By filling thermal insulation material (glass fiber insulation material) between the inner and outer membranes, the overall thermal resistance of the building reaches R20 (compared to about R8 for typical exterior wall insulation in conventional buildings). It effectively eliminates thermal bridges, maximizes insulation performance, and can reduce overall energy consumption by over 80% in certain configurations.

Thermal resistance (R‑value):

R is a measure of how well a material resists heat flow per unit area at a given temperature. It is widely used in building design to evaluate insulation. The higher the R‑value, the better the insulation performance.

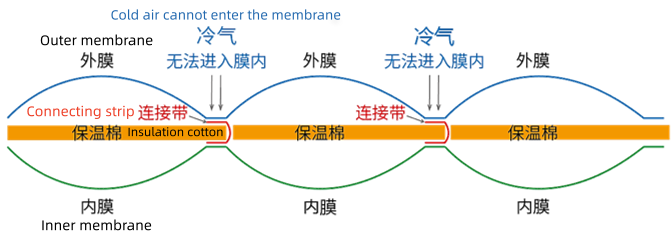

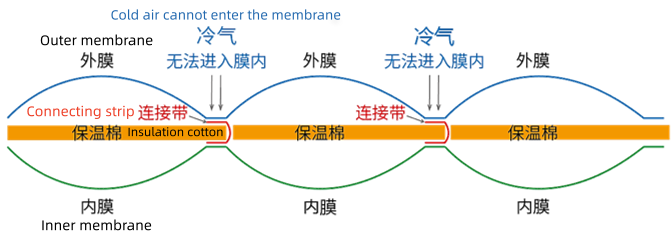

2. Proprietary Membrane Fabrication to Eliminate Thermal Bridges

A connecting strip made of the same membrane material is introduced between the inner and outer membranes, creating a 100–250 mm thick insulating air layer. Combined with an innovative three‑stage high‑frequency welding process and a custom track‑type welding machine, this design prevents condensation and thermal bridges at connection points, improving heat retention performance by about 20%.

3. Patented Airtight Door System (Shenzhen Patent Award)

Broadwell has developed a specially designed airtight door system and corresponding control method for air dome access. This patented solution enhances the enclosure's overall airtightness and effectively reduces internal heat loss.

Winter heating is critical to making a venue both comfortable to use and cost‑effective to operate.

Broadwell air domes are not simply a membrane plus some heaters, but a systematically optimized solution that combines energy efficiency with occupant comfort. With proper design and operation, they offer lower winter heating energy consumption and more predictable operating costs than traditional venues, with clear advantages over traditional buildings throughout the heating season.